Professor

Director, Genomic Analysis Laboratory

Plant Molecular and Cellular Biology Laboratory

Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator

Salk International Council Chair in Genetics

It was long believed the sequence of genes in a genome was all that was needed to understand that organism’s biology. Recently, scientists have realized there’s another level of control: the epigenome. The epigenome is made up of chemicals that dot the DNA, dictating when, where and at what levels genes are expressed. But how these epigenomic tags affect biology, health and disease is still poorly understood. To decrypt the information they contain, researchers still need to answer basic questions about this extra genetic code.

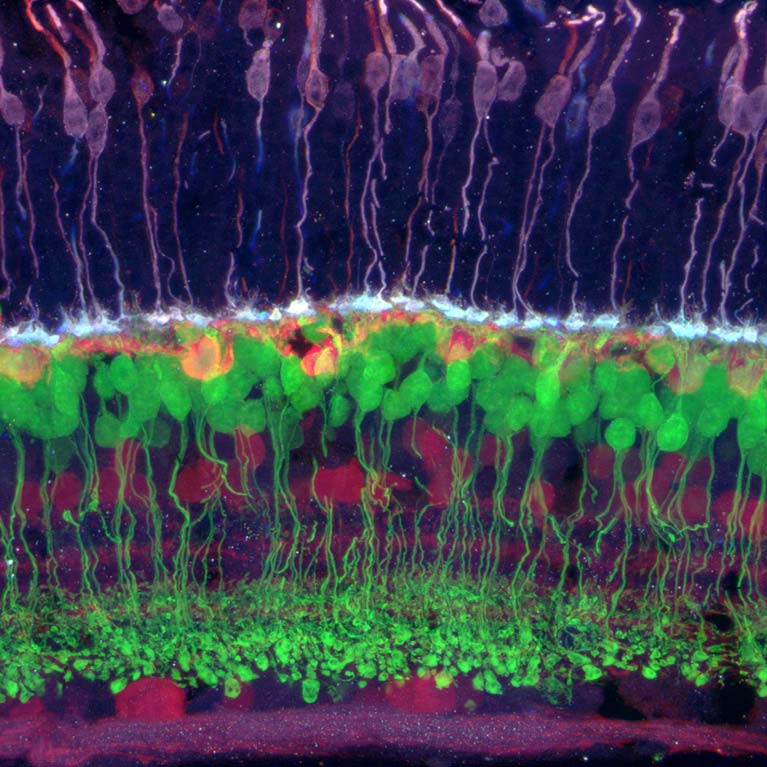

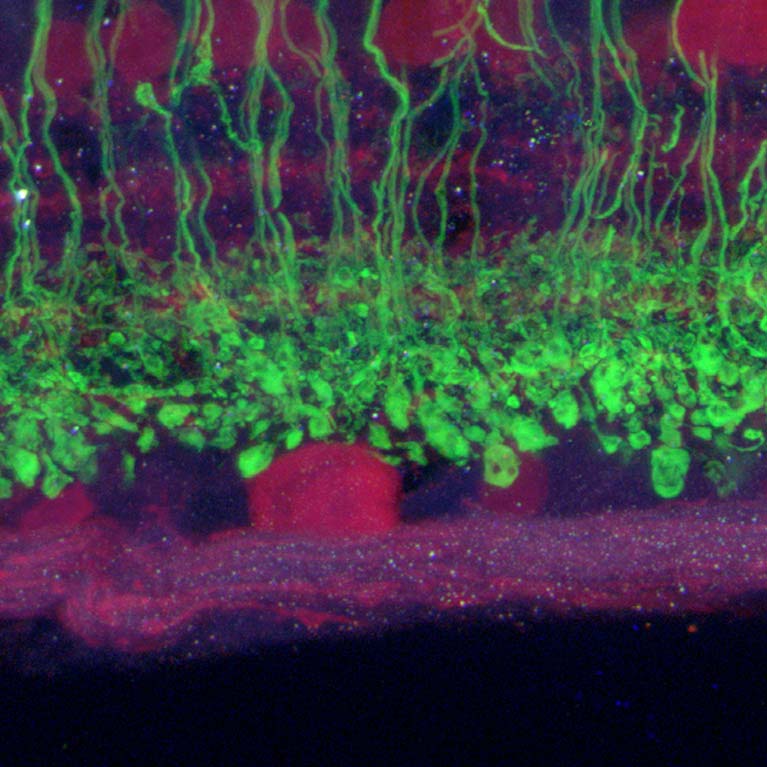

Ecker first became entranced by the epigenome while he was studying Arabidopsis thaliana, a small flowering plant used for basic plant biology research. He and his colleagues wanted to know how many Arabidopsis genes were controlled by DNA methylation—one form of chemical markers that stud genes to affect how genes are expressed. In the process of the research, Ecker realized there was no good way to get a snapshot of all the methylation marks in a cell, so he created a method called MethylC-Seq to map epigenetic tags in any organism. Ecker has now applied MethylC-Seq to questions about epigenetics that span many fields, in particular, the human brain. He was the first to show that the epigenome is highly dynamic in brain cells during the transition from birth to adulthood. Now, he is charting the epigenetic differences between brain cell types to better understand disorders such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease.

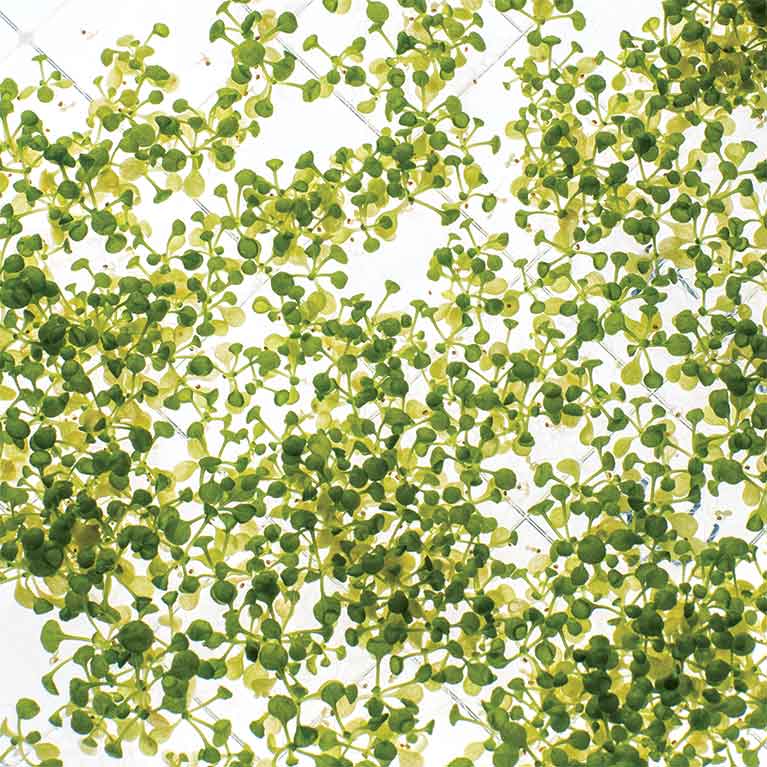

In plant research, Ecker co-directed (and his laboratory participated in) an international project that sequenced the first plant genome. The reference plant Arabidopsis thaliana is now the most studied plant in the world. His group created the “Salk T-DNA collection” of insertion mutations for nearly all of the genes in the Arabidopsis genome, allowing investigators worldwide access to a database of any gene mutation of interest through the click of a button. Additionally, his group discovered most of the genes that allow plants to respond to ethylene, a gaseous plant hormone that regulates growth, resists disease and causes fruit to ripen.

Ecker was also the first to map the entire human epigenome, creating a starting place for understanding the differences between different people’s epigenomes and how these variances could contribute to disease risk.

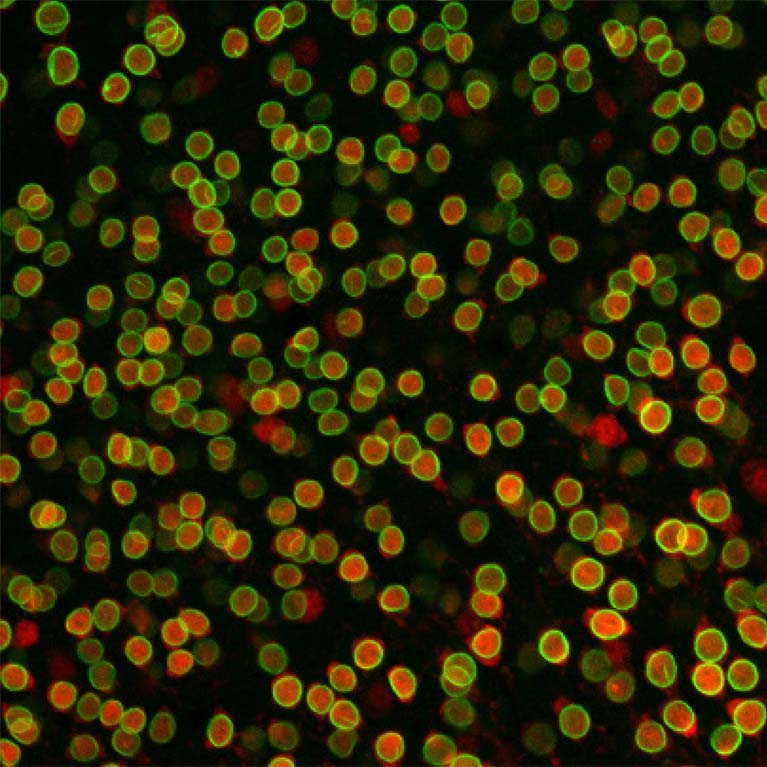

With collaborators, Ecker compared the epigenetic marks on different lines of stem cells to determine which methods of stem cell creation led to cells most similar to the “gold standard” embryonic stem cells. Cells created by moving genetic material into empty egg cells, he found, are closest to this gold standard.

BA, Biology/Chemistry, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, N.J.

PhD, Microbiology, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine

Postdoctoral Fellow, Stanford University School of Medicine